If you were to say that someone was a good UX practitioner, you could mean a great many things. For example, you could be thinking of their ability to run a workshop, an interview or a testing session. You could be thinking of their prototyping, visual or interaction design skills. You might be thinking of their ability to organise and distill complex messy content into a system that makes sense for everyone. You might mean any of these things and more.

UX is wide field that encompases a whole bunch of separate stuff. Usability, Interaction Design, Information Architecture, Content Strategy and more. It produces Personas, User Journey Maps, Prototypes. It conducts User Experience Testing, Diary Studies, Contextual Research, User Interviews… But what joins all this together?

Of course, we know very well what UX is and the role(s) it should play, but if you ask a UX person what they do, they’ll usually make a similar list of sub-disciplines or activities that includes some or all of the items I’ve mentioned above. There isn’t agreement about the reason why this particular group of activities belong together. We don’t have a commonly accepted definition.

Which is why I’d like you to consider my hypothesis: that all User Experience work is a type of negotiation. The type that’s deployed within the process of designing of digital things for people. It certainly isn’t the only type of negotiation used within digital – but it is a key one. But my hope is that this offers a useful way to understand how these myriad and diverse sub-disciplines hang together.

Seeking value for everyone

A prototype is like a peace-treaty. It’s shown to representatives of all the interested parties: the users, the delivery teams, and the business (and any other stakeholders) with the hope of learning from their feedback and changing the details until everyone’s happy. Of course this isn’t high-stakes conflict resolution. It’s only digital. But this work is aimed at the resolution of competing interests nonetheless. The people we’re dealing with aren’t literally at war, but what they value does pull them in different directions – and finding the win-win result can take some working out.

It’s the same with Information Architecture. Let’s say we’d created a new taxonomy. We’d show it to the users to understand whether it matches with their mental model (their language, categorisations and priorities). We show it to the tech team to be sure they can support its features (it’s width, depth or multifaceted structure). We show it to the business to be sure that they’re happy with presenting themselves in this way (are the right elements in the right order in such a way that supports how they wish to portray themselves?)

With an Interaction Design, we might show our early ideas to the users to understand how intuitive or engaging it is. We show them to the tech team to help define how the interaction should behave on different devices. We show it to business stakeholders to be sure that they feel it matches with the brand attributes or strategy that they’re shooting for. Along the way, we iterate – but not just for user’s needs. We change things until there is something that everyone can invest in. As with a peace-treaty, we keep adjusting the elements at play until we’ve negotiated as big a win for everyone as we can.

Identifying ideas vs. executing them

We can think of our agenda as being twofold. We want to

a) identify brilliant ideas and

b) execute them well.

Execution (part b) is usually the most time-consuming and collaborative of the two. And so when web-makers think of negotiation they most often think about this part. Being able to negotiate well in execution of an idea will help push it through production. Compromises are made, but in a spirit of trying to get as much of our original vision implemented as possible. As Alan Cooper put it “Design is a power struggle”.

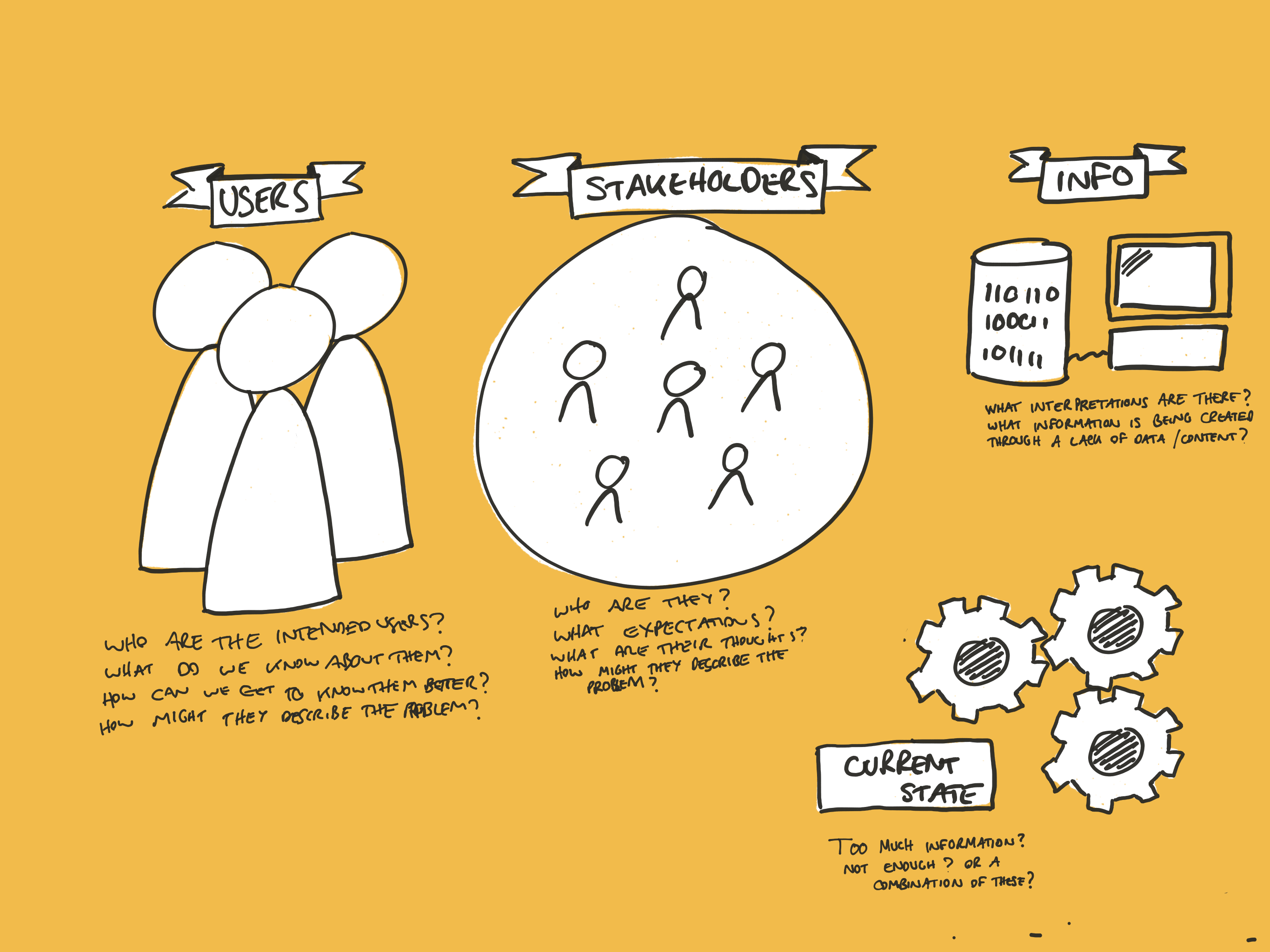

But negotiation is more than promoting our agenda. The most important negotiations happen in the process of identifying what the agenda should be in the first place (part a). An idea can’t be that brilliant unless it represents a satisfactory negotiation of the competing interests for all interested parties. Whether or not you do UX, identifying a valuable idea involves a deep understanding of the trade-offs at play within all the people that surround it.

Let’s say you done some research to understand what a particular set of users need. You then create a prototype and improve it with several rounds of user testing. You get to a point, where you’re convinced that you’ve got a brilliant solution, only to discover that the development team can’t implement it, or the business can’t sell it or there is some other reason that it can’t ever go into production. Let’s be honest, we’ve have all been there. In those situations, the solution that you arrived at was never brilliant. It was a waste of time.

Starting with the user need?

Here’s why. We don’t ever really start with the user need.

Ok, so we do create user journeys that start with a user intention, but the next step is always an interaction with our (or our client’s) product or service. Because there are always other interests at play, the first of which is usually an organisational or monetary goal. We should stop pretending that we care most about the user and be more honest about the need to weave other interests into the mix.

The title UX designer / consultant may be an unhelpful one here. It might tempt UXers to picture themselves as an authority who represents the user interest, the person closest to the research whose job it is to determine what each digital experience should be. They might be diligent and talented and even a great craftsman but still produce terrible work simply because they believed that user interests are the ones that matter most.

I’ll bet you’ve met UX people like this. They’re the one’s who’ll roll their eyes when they don’t like a decision, who’ll dig their heels in when things don’t go their way. They’ll get stuck on what they think they saw in the research, believing (wrongly) that this is the only light that needs to be shone on the situation. Ultimately, their inability or unreadiness to negotiate gets in the way of producing good work. And this is especially annoying if you believe like me that negotiation is precisely what they’re their to help with.

UX research, design or strategy delivers value when it considers all the interested parties. The work is valuable if and only if it provides insights to guide the win-win.

Getting to Yes

The world’s best selling book on negotiation skills is called Getting to Yes. It was written by Roger Fisher and William Ury and has been in print for over 30 years. It outlines an approach to negotiation in four steps:

1. Separate people from the problem

2. Focus on interests, not positions

3. Invent options for mutual gain

4. Insist on using objective criteria

This closely maps to the domain of UX, where the approach is:

1. to understand context, emotions and needs, (EMPATHY)

2. to look beyond what people say they want, (ANALYSIS)

3. to learn through iteration and feedback, (IDEATION)

4. to do research and validation. (QUESTIONING)

Naturally these things aren’t the exclusive domain of people with UX in their title. Everyone is responsible for negotiation. However, it is useful to have a specialist negotiator: an expert mediator, with experience of delivering successful outcomes through the approach outlined above. They might be a UXer or a Product Manager or a Marketeer. It doesn’t matter. What’s important is that these four things happen (not whether to call them UX).

Let’s look at each negotiation principle in turn.

Separate people from the problem

Given that humans are always involved (be they clients, collaborators or customers), there will always be people-problems that come along with the design challenge. This principle helpfully reminds us that both must be dealt with separately to avoid the possibility of mistaking a people-problem for a design challenge or vice-versa.

Great UXers nurture their empathic listening and facilitation skills to this end. It helps them to encourage all voices to be heard, whilst bringing focus on the most relevant questions. This is not about filtering out emotion. It’s about zeroing in on the elements that are most pertinent (be they facts, hypotheses, tastes or emotions or whatever else). When particular people-problems arise these are never brushed under the carpet. They are separated out for later discussion, so that the more important matters can stay centre stage. This is vital stuff in a workshop, a user interview or when designing in teams.

Imagine you’re facilitating a collaborative sketching workshop, and there’s one person who isn’t playing nicely. They squash all ideas before they get a chance to be developed. It is your job to notice and try to deal with this situation, right?

Also the case, when say, you’re facilitating a testing session, and the user gets nervous in a way that prevents them from being able to talk freely about their experience. Ideally, you’ll find a way to put the participant at their ease so that you can more value out of the interaction.

Focus on interests, not positions

“Getting to yes” gives a nice example to illustrate this principle. There are two sisters arguing over an orange. Each refuses to back down and eventually they settle on dividing the orange in half. It later emerges that one of them wanted the fruit and the other wanted the peel. If they had shared what they were interested in, they could have worked out a better solution to their problem.

Great UXers get this too. Picking out patterns in qualitative or quantitative data requires considerable focus and a willingness to jump into the messy detail. You simply can’t stay on the surface. The real action is in the myriad competing interests that jostle and urge us in contradictory and maddening ways.

So if you’re conducting user experience testing then you should know not to invite users to express opinions. You ask them to complete tasks, and then enquire into their motivations, expectations, perceptions and behaviour as they think-aloud their way through your prototype or site. In this way, you hear so much more of the real story of what they care about.

Similarly, if you’re facilitating a design critique with your client then you need to frame things carefully to get the feedback you need. Even if they are designers themselves, you’re not after an assessment of your particular skills or tastes. So you ask how the work helps their underlying interests – their goals or requirements. And you never ever ask people whether they like your work.

Invent options for mutual gain

Negotiation involves coming up with lots of options: spreading the net as wide as possible, before narrowing the field and then picking the best candidate from the bunch to proceed with. The best option being the one that provides the maximum gain for all interested parties.

This is another of the keys to successful UX work. Options are explored early with the hope of finding a good direction before too much investment is made. Ideally you’ll exhaust lots of options in collaborative sketching sessions, where at least part of the point is to fill the bin with discarded ideas before they can get any further. Each idea gets you closer to something that can perhaps be taken forward into prototyping, where it gets explored further still through testing and client reviews. All with the view of finding something that delivers value for everyone.

Most UX activities involve the UXer testing their work by going back and forth between the interested parties – continually learning and considering new ways to provide that mutual gain. (Side note: an exception might be Co-design Workshops, which offer a unique way to exercise this principle – where users, implementors and the client work side-by-side to design product or service interactions.)

Insist on using objective criteria

This principle is concerned with bringing in external expertise or evidence. In situations where it’s difficult to see or agree on a way forward, we can at least agree on some objective way to provide the guidance we need. An approach that can save us a lot of unnecessary debate and posturing.

Sometimes it’ll be cold scientific fact-checking that can give us an answer. Other times it’ll take softer, qualitative measures. But it will always involve research, testing or validation of some kind.

In UX, the evidence being considered is usually from the point of view of the user’s interests. We’ll say that a design works if we have evidence that it accords with the intended user’s mental model or if more testing participants manage to complete usability tasks successfully. But these criteria could also be described in terms of business interests as increased user engagement with the product or increased conversions of some kind.

The objective criteria for success is that mutual gains are reached. We don’t think up ways to help the user in isolation from helping the product or service. It’s never a coincidence that great UX is good for business.

Anyone can do this?

UX practitioners, perhaps more than anyone else, experience imposter syndrome. After all, it’s getting easier and easier to create fancy looking flowcharts and interactive prototypes. The barrier to entry feels alarmingly minimal.

The difference between good and bad UX work is the amount of problem definition and solving that it does. To tackle this properly, someone (or several people) must take on the role of forming the bridge between all of the interests at play. They’ll need the empathy it takes to separate people from the problem. They’ll need to have the analytical skills it takes to focus on interests and not positions. They should be ever-eager to invent options for mutual gain. And they should be able to validate and refine their ideas by agreeing and using objective criteria.

Negotiation is more than just a core UX skill. Negotiation is the skill of UX. It joins all the separate strands of UX activity together. Whether you’re running a workshop, conducting a piece of user research or creating a prototype, the work is meaningful and useful in so far as it seeks out a win-win for all the interested parties. In the end this is not the work of a genius designer or team working in isolation (crafting amazing solutions from some great vision that comes to them). When it works best, UX design is nothing more or less than a type of principled negotiation.